I first joined the videogame industry back in 2006. One thing I’ve learned is that whether you’re building your first prototype or polishing a near-finished release, game design is where good games become great. Too often, indie devs get lost in the features and forget the fundamentals.

In this article I’ll break down 10 game design principles (most of which I’ve had to learn the hard way). If you’re serious about improving as a video game designer (or just want your next project to thrive), these principles are for you.

Indie Game Development is all About Player Experience

Let me save you six months: nobody cares about your clever mechanics if the game doesn’t feel right. Before you even think about systems, sit down and ask yourself: what should the player feel in their first five minutes? Are they tense? Empowered? Maybe they’re even confused. This feeling will be your emotional anchor. Everything else (combat, UI, even the jump height) should bend around that. I’ve seen time and time again indie devs build their game around features they thought were cool – but forgot the player was meant to be having fun, first and foremost.

Nail the Core Gameplay Loop Before You Expand

Don’t get distracted by your worldbuilding wiki or your 300-page lore doc just yet. It’s tempting… I know. If the core loop of your game isn’t satisfying to the player – none of your cool worldbuilding will mean anything. Trust me, I DM for fun – I love to procrastinate pouring months into worldbuilding, narrative, and additional systems – but indie devs have to start lean. A fun core loop first, and the rest follows.

Your core loop is the heart of the game. It’s the thing the players will do hundreds of times without even thinking. Move, shoot, dodge. Mine, craft, build. If it’s not clean and engaging then everything else is just scaffolding on a crumbling building.

Prototype it ugly. Make a greybox and playtest it until you’re sick of it. If you’re still having fun? That’s your sign to build more. Otherwise, strip it back and try again.

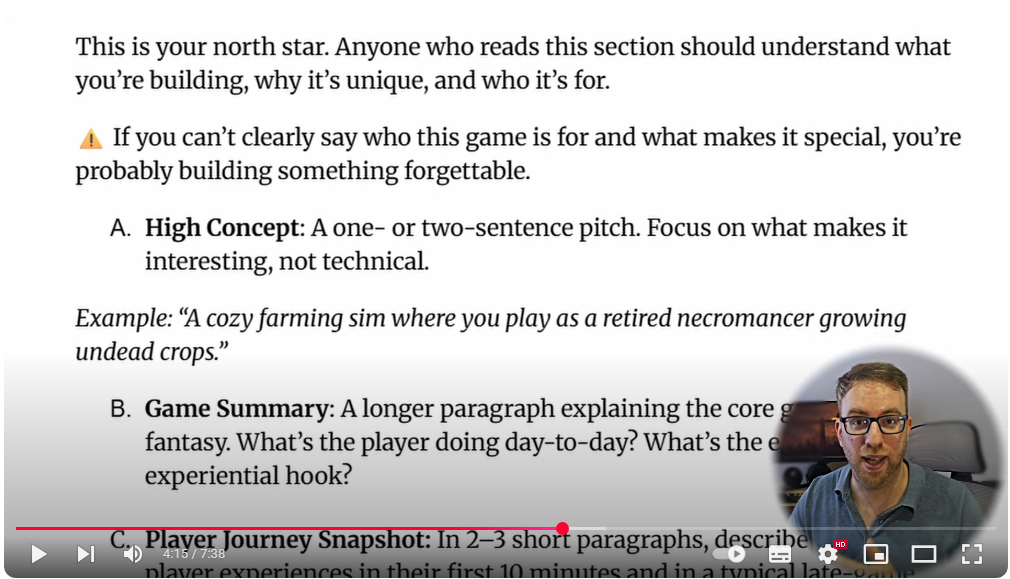

Your Game Design Document Is a Shared Brain

You’ve probably seen me wax lyrical about the importance of GDDs. Here I go again. The truth is, game design documents are fundamental to your game’s success. I’ve been there. The GDD is the brain of your team that you, and anyone else involved with your game, plugs into.

You know when somebody asks you how the combat system works and you think, “Didn’t we already cover this?” That is the GDD’s job. It’s how your UI designer knows when what elements to make jump – without asking the designer each time.

You need this at the start, and you need it all in one place. Update it as you go. A messy and evolving game design document is much better than a polished one that’s out of date.

Plan For Change – Your GDD Should Evolve

One of the few things more certain than features being late is features being changed. The mechanics you were so sure about early in development will probably end up getting scrapped or reworked into something completely different by the end. But hey, that’s design.

Your GDD isn’t a sacred text or bible – it’s a living document, and as close as you can get to a conversation with your future self and team. It should shift and show its battle scars. Real development lives in the drafts and changes made along the way.

We all know that the game development process is chaos – and your GDD should probably reflect that. Changing and updating a paragraph today could save you hours in the future, so do it. None of us want to live in regret.

Use whatever tools you need to, whether that’s Notion, Trello or Docs – but make sure it’s all kept in the same place. Your ideas need to be readable, trackable and changeable.

Define Clear Design Pillars Early

Think of a design pillar as your project’s, well, pillar. They serve to hold and shape the building that is your game – and, without them, you have nothing to build around. Deliberate pacing. Permanent consequences. Resource-driven tension. That kind of thing. When things get messy (and they will get messy), these short statements will be a north star for you. If a mechanic doesn’t support them, cut it.

Pillars settle design debates quickly. ‘Cool idea. Does it fit the core pillars?’

Don’t wait to identify these. Set them early and stick to them. Print them out and stick them on a wall. If your whole team isn’t designing towards the same emotional goals, you’re building disconnected features that just so happen to live together.

Game Designers Build Around Constraints, Not In Spite of Them

Every game, at some point, hits a wall: whether that wall is budget, time, engine issues or motivation. You’ll have two options. Crash into it… or steer with it.

The best indie games capitalise on their limits. No budget for cutscenes? Cool, tell your story through the environment. No voice acting? Let silence and pacing do the heavy lifting. Small team? Focus on depth, not scale. Constraints don’t have to be obstacles – in the end they may be what makes your game a success. Some of the most iconic games exist because of their limitations. Think of Undertale or Obra Dinn. They had to get clever, and you’ll probably have to too.

The more honest you’re being with your limits, the more focused your design becomes. Embrace what you can’t do and you’ll come up with ideas you would never have thought of before.

Every Gameplay System Needs A Purpose

Feature bloat is the fastest way to dilute a strong core. New mechanics aren’t new toys – they’re whole new systems you’ll need to balance, polish and justify. If it’s not strengthening your core loop, supporting a design pillar or serving the player fantasy… It’s just noise and needs to be cut.

Look at the most memorable indie games – rarely do they overwhelm you with systems. Dead Cells knows not to waste your time with crafting tables. It doubles down on its unique identity. Every system needs to earn its place, or be cut.

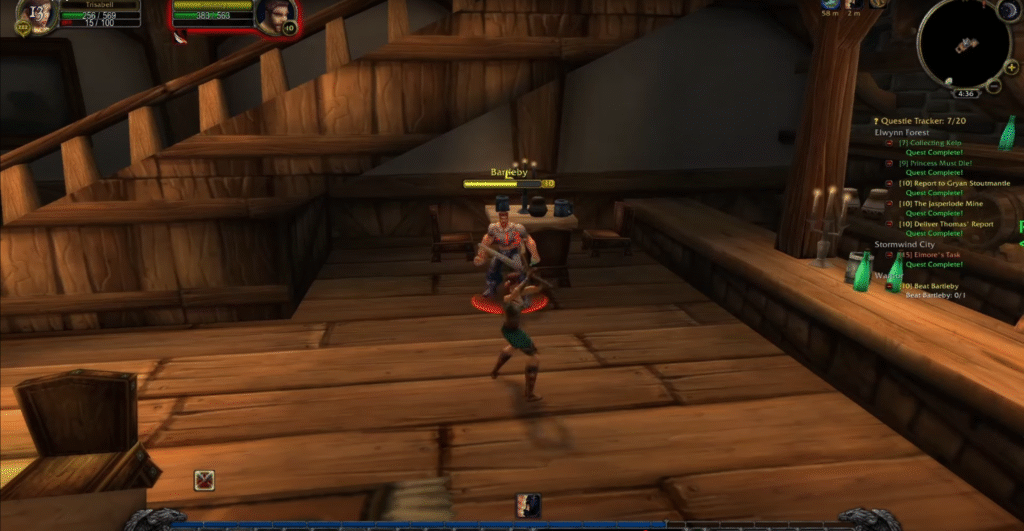

Design Progression as a Journey, Not Just Stats

Too many games fall into the trap of shallow progression, with flashier weapons and bigger numbers. Those may feel good in the moment (and this serves a purpose), but eventually you’ll realise… nothing’s really changed. You’re still doing the same thing, except maybe this time the pop-ups look slightly different.

The best progression systems evolve the game. They make the player feel like they’ve grown with their character. Maybe they’ve unlocked and mastered a tricky combo that felt impossible an hour ago. The power shouldn’t just be coming from arbitrary numbers – but from the player.

Good progression is paced like a story of its own, with peaks and valleys where the players go from feeling unstoppable to questioning it all. It’s a journey that can keep the players engaged far better than a never-ending supply of stat boosts. When the player finally unlocks a new ability or upgrade, it should mean something to them.

Communicate Through Feedback Loops

Games are conversations.

Every time the player presses a button they’re asking the game a question – and it’s your job as the game designer to answer them immediately and clearly. At its core, that’s what player feedback is all about. It’s not flashy VFX or sound cues (though those can help), but a constant stream of responses that tell the player that they’re being listened to. It could be a satisfying hit noise or an enemy staggering when you block their attacks. This is all information telling the player ‘you’re doing it right’.

When feedback is missing, players become confused. The most polished games over-communicate to their players. It isn’t about noise, but, rather, clarity. The player needs to consistently feel the game reacting to them, listening to their questions and giving them the answers that they want.

Design For Clarity, Not Cleverness

If your mechanic needs a paragraph of explanation before your players can grasp it, it’s probably clever. But not clear. As a game designer, your job isn’t about hiding complexity from the player, but instead presenting it in a way that’s intuitive.

Clarity doesn’t mean dumbing things down – it means giving players the right information at the right time. Rely on visual language, consistency and feedback loops to make your systems clear – even when they’re challenging. The moment the player can’t read what your game is telling them, they’ll bounce. Be clever, but be clear first.

Conclusion

Game design is tough. We can all get carried away with our flashiest, smartest ideas – but game design is the process of choosing the ones that are right for your game, and knowing why they matter. Every part of your game, from mechanics, to game feel, to your visual identity, should back up the experience you want your players to have.

It doesn’t need to be perfect the first time around. It’s a process. Don’t be scared to be honest with yourself, your team and your game. Nail the fundamentals. Test early. Iterate often. And most importantly: design with purpose.